What is RILx?

RILx is the Response Innovation Lab network’s annual gathering and one of the few global events dedicated to exploring local humanitarian innovation systems.

Hosted by the Nepal Innovation Lab and World Vision, RILx24 will bring together staff from RIL platforms in nine countries, global peers and partners, including leading humanitarian agencies, and leaders in social impact innovation from Nepal and the wider South Asian region to collaboratively explore the dual themes of ecosystem building and business modeling. Over the course of three days, this diverse mix of thought leaders will exchange experience, insights and ideas about these two topics critical to the scaling of impactful solutions and will collaborate on identifying practices worth amplifying and generating new models to pilot.

RILx24

Kathmandu, Nepal

The Malla Hotel

2024 September 17-19

Supported in Nepal by

The Nepal Innovation Lab

World Vision International Nepal

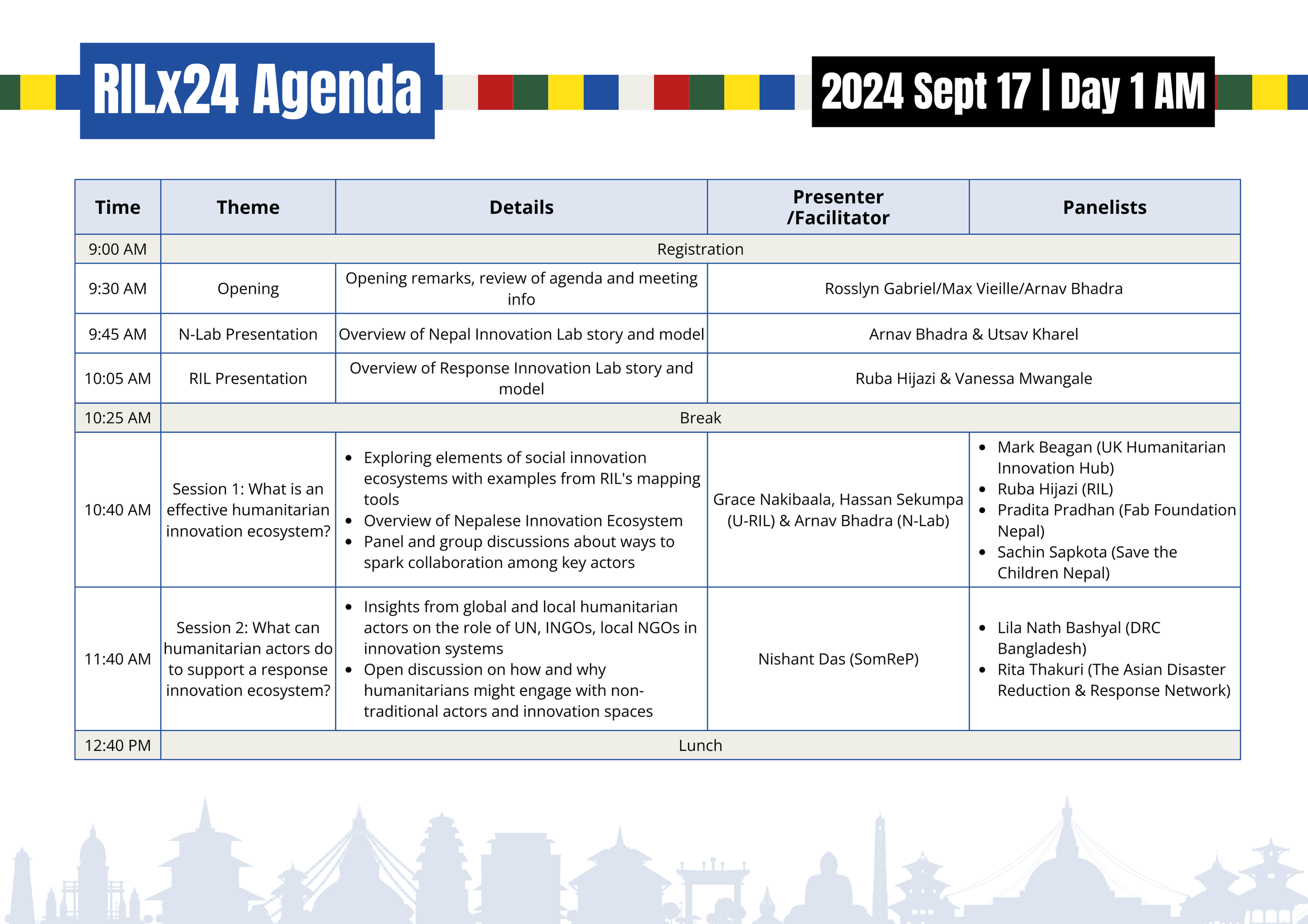

Agenda at a glance

-

Day One will take attendees on a deep dive into social impact innovation ecosystems -- their composition, how they function and what they can do to facilitate the scaling of effective solutions across multiple pathways. We will be particularly attentive to the collaboration models that local innovation hubs, social entrepreneurship support organizations and other specialized actors have developed to boost social impact.

-

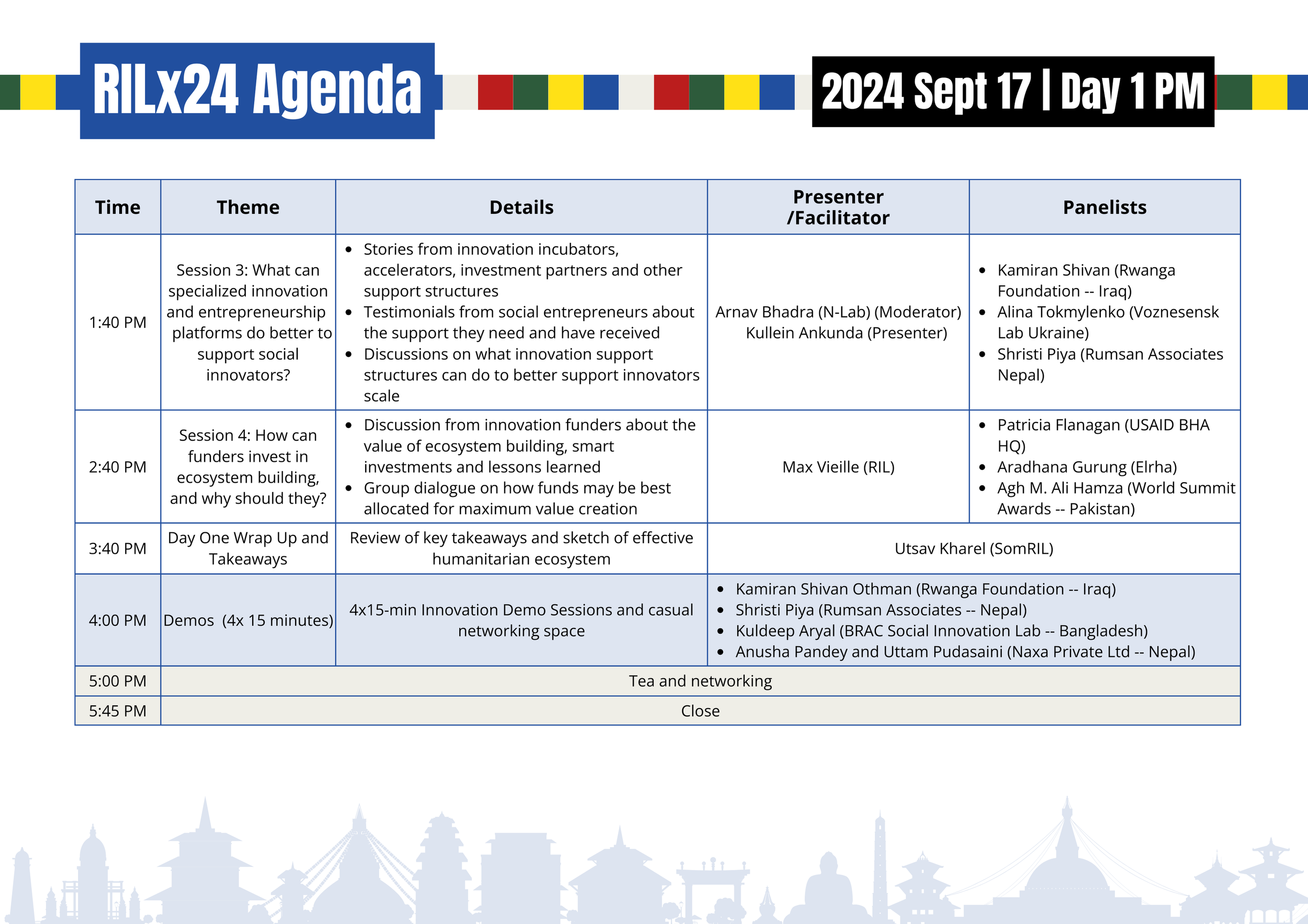

Day Two will shift the focus to what business models offer the best chances for different types of social innovations to achieve financial sustainability and reach their scaling potential. Mixed and hybrid systems where private sector, government, non-profit and community actors contribute to the funding of the solution will be particularly highlighted.

-

Day Three will draw from the previous two days’ worth of exchanges to further explore some of the most promising approaches and introduce new Big Ideas, smart “hacks” or opportunities to try something new.

RILx24 Highlights by Themes

-

Before discussing the commitment to building an effective humanitarian ecosystem, we must define what it entails and identify the available tangible and intangible resources for fostering relationships within it.

An effective humanitarian innovation ecosystem is diverse, integrating a wide range of stakeholders to address real-life challenges and facilitating collaboration. Local partners are crucial, as they possess a better understanding of the local context.

Innovation encompasses more than just products or services; it is a process that requires input from various sectors. The public sector, particularly governments at all levels, plays a vital role by shaping public policies, while the private sector contributes ideas and sustainability to programs. It's essential to recognize how innovations in the development sector differ from those in other fields, including factors like piloting timelines and definitions of success. Innovation in development and humanitarian contexts operates differently than in other sectors.

Instead of reinventing the wheel, an effective ecosystem encourages new ideas and seeks sustainability. Three investments are to be prioritized if humanitarian innovation ecosystems are to become more effective:

on-site research that provides clearer and more precise understanding of challenges and the effectiveness of solutions;

a knowledge sharing system that helps local supply and demand for innovative solutions connect with each other as well as with global partnership opportunities;

mechanisms to increase community engagement in the innovation process to ensure more feasible and sustainable solutions.

-

There are commonalities and differences in the roles of locally-led humanitarian actors and international actors in a response innovation ecosystem. The definition of innovation as a challenge-based, social impact-focused process is common across both sets of actors, as is the concern that humanitarian and development funding do not allow much room for experimentation and failure. Donors are asked to provide more of an enabling environment in their awards and their policies to leave more room to try out innovations, which might range from bold new ideas to adopting emerging solutions that are proven to work. There is also broad agreement that humanitarian actors of all types need to learn to “fail better” and to share information of what has worked and what has failed in a particular context. This will require revisiting MEAL/M&E tools that are not designed to capture early results and adoption of solutions by communities.

The role of INGOs and Local NGOs (LNGOs) differs in how each can generate partnerships in the wider ecosystem. As DRC Bangladesh demonstrated, an INGO is well positioned to broker partnerships with global actors who have interests in a particular context that bring resources, expertise and the capacity for system transformation in that area. Meanwhile, ADRRN made the point that LNGOs are a critical link to communities in vulnerable or crisis-impacted areas and have the ability to co-create solutions that are uniquely adapted to the context and have a higher sustainability potential.

-

Social innovation and entrepreneurship platforms must bring added value to the innovators who seek their support and to the ecosystem at large. More than funding and technical assistance, these organizations offer opportunities for networking and visibility, allowing start-ups and social enterprises to generate new partnerships and establish trust and credibility with stakeholders.

These platforms can also help steer more resources and attention to a context by providing market intelligence and other valuable information to potential investors, donors or clients. Too many duplicative platforms can render the ecosystem too complex for external actors, however, so organizations seeking to create one should first try to partner with existing actors.

Incubators, accelerators and hubs also need to provide the right kind of guidance to innovators and entrepreneurs, from people who understand their journey and the context. They should also engage with the government to facilitate the proper registration of the businesses (or NGOs) that they support, while possibly also advocating for more enabling policies.

For solutions to scale, a thorough understanding of the demand for different types of innovations in a particular context is important and must be built into the selection process. By championing the most promising ideas, despite limited funding, these platforms can help steer the system toward the most sustainable and scalable solutions.

-

The perception of innovation by donors has been evolving from a portfolio approach that focuses on the merits of individual solutions to a broader understanding of innovation as a process that can improve impact, facilitate localization and lead to broader systems change.

There has also been a welcomed shift to embed innovation processes at the community level, where the people impacted by crisis and fragility best understand the impact of challenges and the potential for durable solutions. The challenge remains of how to scale these solutions across communities and what roles global, national or response-level actors could play in maximizing the impact.

Humanitarian donors are conscious of the limitations of traditional funding mechanisms, especially compliance-driven grant funding, and are actively exploring more flexible mechanisms like co-creation and innovation prizes.

Meanwhile, private investors clearly see the benefits of investing in ecosystems to improve the quantity and quality of emergent social enterprises but also see that non-profit actors can harm these entrepreneurs by de-prioritizing profitability and thus undermining long-term sustainability of these solutions.

-

When there is market failure, using the traditional market approaches will not work. In times of great disruption and humanitarian crisis, aid actors can “create” markets that operate differently than the norm, through the provision of free or heavily subsidized goods and services to populations that cannot presently afford these at market value. These “artificial” markets are temporary and/or can shift based on aid funding flows and priorities, however, so sustainable solutions need to eventually function and succeed in a more traditional economic context. Therefore, humanitarian actors must prioritize business models that can adapt to these shifts.

Social enterprises, whether on a for-profit or non-profit model, and their backers need to understand market segmentation and the political economy of the context so that solutions fit within reality as opposed to expecting new economic conditions to emerge. Moreover, understanding the intersectionality in the context of the community being served is important. Geography, gender, economy, level of education... understanding the complexity of the demographics helps the actors truly understand the needs and the demand, so that businesses and the civil society can work better together ensuring that the initiatives being developed can be well integrated into the society.

Mixed models that incorporate aid subsidies or upfront investments that reduce costs or facilitate access can help leverage the strengths of the non-profit and for-profit approaches. However, if a solution is structured as a commercial actor (i.e. a social enterprise), it must be able to demonstrate a potential for profitability as it scales.

-

The true driver of a nation's prosperity lies in the private sector, which now must take a more active role in advancing humanitarian innovations.

Both the private sector and NGOs can leverage their distinct strengths, working collaboratively to enhance each other’s impact and even foster mutual transformation. The private sector offers key advantages: 1) financial resources; 2) leadership skilled in driving efficiency and results; and 3) a robust organizational culture anchored by clear vision and lived principles, exemplified by the adage "culture eats strategy for breakfast." On the other hand, NGOs bring invaluable insights, including: 1) a deep understanding of communities beyond their roles as consumers; 2) the capacity to enable participatory approaches, such as community-led design; and 3) a commitment to social and environmental responsibility.

Innovators call for greater coordination, co-creation, and flexibility in both policy frameworks and ecosystem structures, recognizing the diverse roles and languages spoken by various actors. Looking ahead, trust-based partnerships will be critical to achieving the changes we seek. However, ongoing reflection is necessary: “How do we cultivate such trust?” and “Who exactly constitutes the private sector in this context?”

-

When discussing sustainability, it is essential to address both the "needs" and "demands" of the community. Innovations must have the capacity to evolve independently, adapting to multiple needs rather than being limited to a singular focus. This is why innovations exist in different stages. Sustainability is also about accessibility—ensuring that social innovations are truly available to the communities they are meant to serve. Additionally, fostering a culture of scientific thinking and evidence-based decision-making is vital for long-term sustainability. Co-creation with communities lies at the heart of such solutions.

This question may not have easy answers, but we do know the common factors that hinder sustainability. One major obstacle is the inability to effectively market or "sell" innovations, often due to issues with storytelling or financial constraints. Another challenge is the failure to adapt to necessary changes as they arise. Sustainability also suffers when there is an imbalance between inputs and outputs, or when stable funding—whether from external sources or self-sustaining mechanisms—cannot be secured. Conflicts between ownership and leadership roles can further complicate matters, as can the absence of community-based, human-centered solutions. Ineffective stakeholder engagement and difficulties in managing contractual relationships are also significant barriers. Additionally, excessive dependence on a single entrepreneur or a small group of funders can weaken long-term viability. Finally, losing sight of the broader ecosystem or failing to gain cultural and social acceptance can prevent innovations from taking root and flourishing.

The key question then becomes: how do we learn from failures—our own, those of others, and those across different contexts?

-

Innovators must recognize the importance of consistently delivering value to stakeholders, as this is essential to avoiding the "innovation grant trap." However, a "grant mindset" often risks overshadowing the broader goal of building sustainable businesses, shifting the focus toward securing grants rather than long-term growth. Overreliance on grant-based funding can limit development and potentially erode trust with government partners. Therefore, diversifying funding sources is crucial. Moreover, innovators should ensure that open-source solutions are carefully localized and adapted to specific contexts, as directly applying them without consideration may not yield the desired results.

The broader humanitarian ecosystem can also do more to support innovators in this regard. Capacity building is critical in helping innovations move beyond traditional business models, ensuring that solutions remain human-centered and aligned with actual community needs. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that innovation should not be restricted to a single humanitarian agency. Allowing multiple agencies to adopt and scale these solutions can amplify impact and enhance sustainability.

The discussion also highlighted key traits of successful innovations that have managed to scale and achieve sustainability. These include addressing genuine community needs, obtaining the necessary certifications, and integrating effectively with existing humanitarian procurement processes.

-

Continuous learning and knowledge sharing are crucial in the humanitarian and development sectors. However, the current system faces challenges in effectively capturing and applying lessons learned, as it is primarily designed to respond rapidly in crisis situations rather than to engage in transformative learning. At the response level, there is a clear need for real-time learning, alongside innovative methods for capturing and applying insights during humanitarian operations, rather than relying solely on after-action reviews.

Greater efforts should be made to localize learning and knowledge-sharing. Creating interdependence between international and local entities is essential, supporting the sharing & application of local knowledge and resources while also bringing in global expertise. This approach fosters a more balanced and sustainable exchange of insights that strengthens the overall ecosystem.

-

Many local organizations have been negatively impacted by traditional development modalities rooted in neocolonialism, highlighting the need for more flexible, community-driven approaches. This shift calls on the broader ecosystem to explore process and technological innovations that can help local organizations build capacity, trust, transparency, and accountability.

Decentralized network, platform, or hub models can effectively facilitate the exchange and showcasing of ideas. However, the challenge lies in the proliferation of similar platforms. The focus should be on integrating local communities into the humanitarian system while addressing capacity gaps and tackling colonial or racist elements that have hindered equal participation and contribution. Additionally, the issue of innovation ownership must be addressed.

Innovation and good ideas can arise from South-South exchanges, not just North-South dynamics. Indigenous and local knowledge should be recognized and integrated, rather than needing to prove their effectiveness and gaining acceptance within the existing development frameworks. Implementers must remain open to community needs, acknowledge power dynamics, use language and communication that resonates with local communities, and recognize the potential of local innovators, whose perspectives may differ from those of more "advanced" innovators.

RIL Q&A

-

RIL is not a new NGO – we are a collaborative initiative between Civic, World Vision International, Oxfam International, Save the Children International and Danish Refugee Council. RIL is not a registered entity and does not have its own bank accounts, employees, etc…

-

RIL adopts a decentralized, network model of management. Each Response Lab is managed by one of its global Member organizations via its Country Office. For instance, the Iraq Response Innovation Lab (IRIL) is hosted by Oxfam Iraq who recruits and oversees staff, raises funds and manages its budget and sets its strategic objectives (in accordance with the Global RIL strategy). The small RIL Central Support Unit (i.e. its HQ) is hosted by Civic and is comprised of a Global Director and two Regional Managers who provide support to the Response Labs, represent RIL gobally and regionally, help mobilize resources and partnerships, and maintain global systems (RIL website, intranet, toolkits).

-

RIL is entirely funded by grants or fee-for-service contracts, with funding primarily being mobilized by individual Response Labs through their host organization’s (e.g. WVI, SCI, OI, DRC) fundraising systems. The Central Support Unit is funded through the provision of technical assistance to the Response Labs to be included in their grant funding, as well as some limited fee-for-service agreement to external actors.

-

RIL platforms are designed to be largely demand-driven and have worked on addressing challenges from nearly all recognized humanitarian sectors. Over time, it has developed a particular focus on displacement and climate adaptation/resilience programming but will continue to be open to working on any challenge area significantly impacting vulnerable populations.

-

RIL is built to engage with all types of actors who are present in the humanitarian innovation ecosystems it serves. This has included UN agencies, national governments, universities, private sector actors, donors, local NGOs, social entrepreneurs and other innovation hubs. RIL’s methodology has a particular focus on engaging with the leading implementers of humanitarian programming in order to better understand the demand (and resources available) for different types of solutions.

-

Initially designed to work in any humanitarian emergency, RIL has found it is most impactful working in prolonged crises, complex emergencies and the reconstruction phase of acute disasters. Over time, our work has drifted into the Nexus, Resilience and DRR programming spaces, particularly as contexts evolve. RIL Response Labs will continue to focus on fragile settings with underdeveloped innovation ecosystems where we can add clear value. In case existing social innovation platforms are in place and interested in adopting our approach, we can invite them to join our network as Affiliate Facilities.

-

If you are working in a context that meets the RIL criteria (e.g. a humanitarian or “nexus” setting with a viable but underdeveloped innovation ecosystem) and are from one of our global Member organizations, you can engage with the RIL Executive Committee contact person to stat a conversation. If you are from an external organization and there is no existing RIL platform serving your context, you may reach out directly to the RIL Central Support Unit (info@responseinnovationlab.com) to notify us of your interest in opening an Affiliate Facility.

-

Each RIL Response Lab has dedicated staff based in the location that they serve. You can find their contact information on the RIL website (https://www.responseinnovationlab.com/wherewework).